But that is the situation we are facing, unfortunately. The large-scale use of state subsidies was absolutely the right thing to do. Without fast and comprehensive support in the form of subsidised pay for those working reduced hours, many employees and self-employed people would have suffered much more dramatic falls in income, with a corresponding effect on

consumption.

At the same time, the central banks approved the increase in government debt and averted any insolvencies and a resulting banking crisis by making targeted purchases of corporate bonds.

The support promised for what turned out to be a very long time also laid the foundation for an encouragingly rapid rebound in the manufacturing sector. But the latest economic data clearly indicates that, with the exception of China, the pace of economic growth has recently fallen increasingly rapidly, including in important European countries such as France, the UK and Germany.

At the same time, the service sector is causing more headaches as time goes on, despite or perhaps also because of the drastic efforts being undertaken to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic from spreading any further.

In a departure from previous patterns, this time it is the tertiary sector and not the manufacturing sector that is proving to be the economy’s Achilles’ heel. The pandemic has not only highlighted modern service companies’ vulnerability and their reliance on a secure healthcare system, but also shows how existentially important the generation of income in the service sector has become for economies. Although some of the negative effects can be offset using different models of working such as working from home, this is not enough for the pulsating dynamism of a productive beehive. A recovery in the service sector also has much less of an impact on other parts of the economy, as illustrated by China. China’s service sector has

recovered, but this has not had much of an effect on demand for imports thus far.

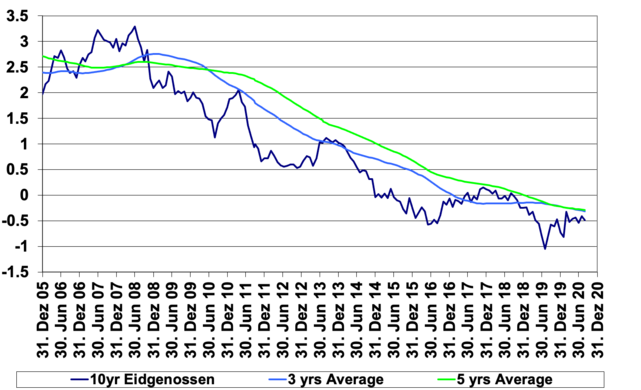

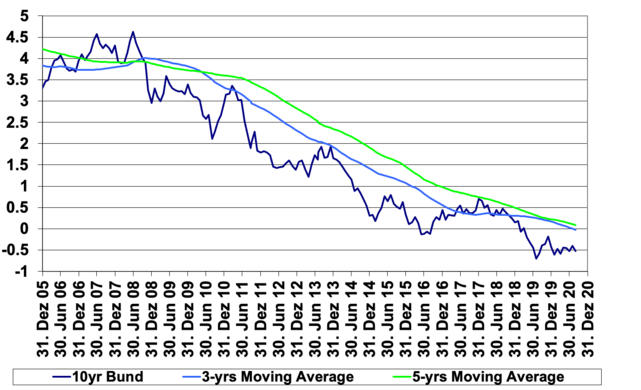

Swiss and German Sovereign Bonds

It is becoming increasingly apparent that only a medical breakthrough in the treatment of the pandemic will enable the service sector to regain its former strength.

And that brings us to our current problem. The resurgence of infection rates in many large cities and highly populated areas has led to the imposition of new restrictions on movement. Combined with the promises made by central banks to keep financing all government debt, the framework for an economic turnaround for the better is in place, were it not for the virus and the reliance on the service sector.

So what’s needed is both a substantial medical breakthrough regarding the treatment of the virus and the political staying power to maintain the support programmes until that happens.

This means that the huge increase in government debt was not only necessary and helpful in the spring. Support is also required now, and at least until the end of 2021 or perhaps for even longer.

So what happens now? Some, like the President of the US, want to significantly scale back the benefits being paid out. The EU, on the other hand, has just decided not to apply the brakes on debt for another year. In terms of domestic politics, the spotlight will increasingly be on the question of how long and to what extent a society should take on more debt in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. The discussion of who should pay for this, when, and how much, has not even got properly started yet. Not only is this question political dynamite, but it also severely limits the funds available for other purposes. People in lower income brackets and precarious employment have already been hit disproportionately hard by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, the revised inflation targets issued by the leading central banks (the Fed and the ECB) suggest that, with interest rates remaining the same for the next few years, we will have to get used to higher tolerated rates of inflation. In other words, distribution issues that have not been resolved by political means are soon likely to be “resolved” by a price/wage spiral.

The international situation is similar. Many poorer, developing countries have no internal financial buffer left.

As the virus can only be tackled effectively at a global level, wealthy countries will need to help finance programmes to combat coronavirus in those developing countries.

Why is this not reflected in the stock markets? Is it the scale and the political will to support the economy combined with a lack of alternatives (TINA) that is causing people to invest in shares, or is it simply a very long-term perspective? In three years, we should hopefully have the coronavirus pandemic more under control. The most recent forecasts issued by international bodies expect the GDP figures seen in early 2020 to be reached again by 2024 at the latest. But there are plenty of other, important challenges to face before we get there. With all the discussions surrounding coronavirus, it is important to remember that the Brexit negotiations between the EU and the UK have still not resulted in an agreement, and that the results of the US presidential election may be anything but clear.

Switzerland’s determined and fast actions in spring have put the country in an astoundingly favourable position. While the strong international ties of Switzerland’s supply sector are unfortunately more of a hindrance than an asset at present, Switzerland’s economy is being supported by its strong pharmaceuticals industry. At the same time, Switzerland’s enormous

financial muscle and attractive living conditions continue to make it a popular destination. At the end of the day, this is also likely to have contributed to the strong performance of Swiss property in an international comparison. Also, given the situation described above, the drive to invest in real estate is more likely to grow than diminish. This will bolster both stocks and

the property market. Partial bubbles will be almost inevitable. So as they say: be invested, but be careful.

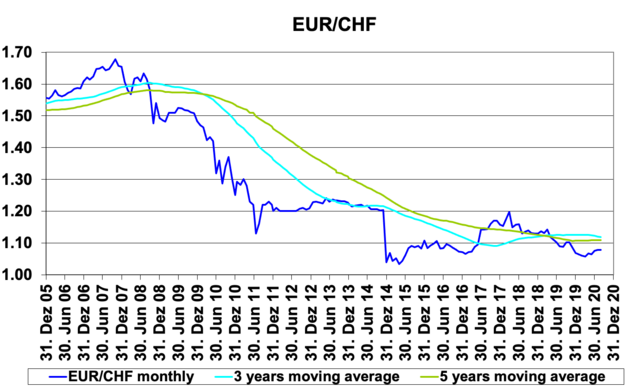

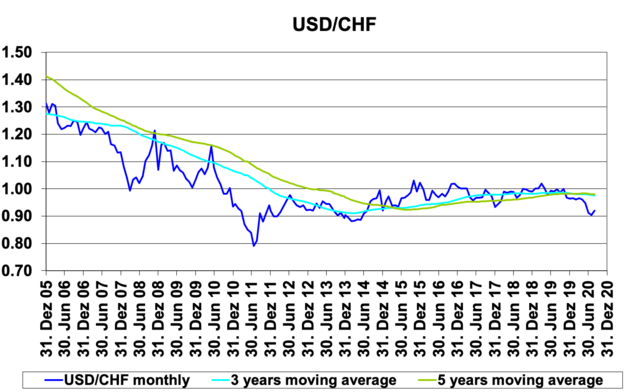

Exchange rates EUR/CHF and USD/CHF

How can it be that western nations have imposed a drastic lockdown and mobilised vast resources to provide temporary support, yet the economy remains firmly rooted to the spot?