After many years of constantly falling interest rates and the option to sometimes borrow capital at negative interest rates, rising borrowing costs are now confronting real estate funds with new challenges – and investors with new risks.

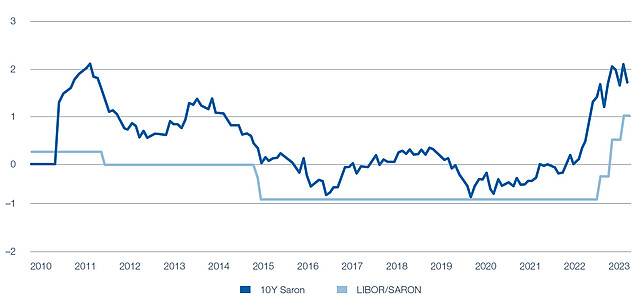

On 18 December 2014, the SNB dared a great experiment by introducing negative interest rates. This was an immediate measure following the scrapping of the euro peg and was intended to stabilise the exchange rate. The falling and negative interest rates made it possible for real estate funds to refinance at ever lower costs. In some cases, the raising of funds even led to an interest credit. The very low interest costs also offered the real estate segment the opportunity to engage in higher-risk purchases and projects and to pursue bolder financing strategies. As shown in Figure 1, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) ended its experiment in September last year with an unusual interest rate hike of 0.75%, therefore raising the prime rate to plus 0.25%. The current prime rate is 1%, and expectations are that this rate could be raised further by between 25 and 50 basis points as early as March 2023.

Different financing strategies

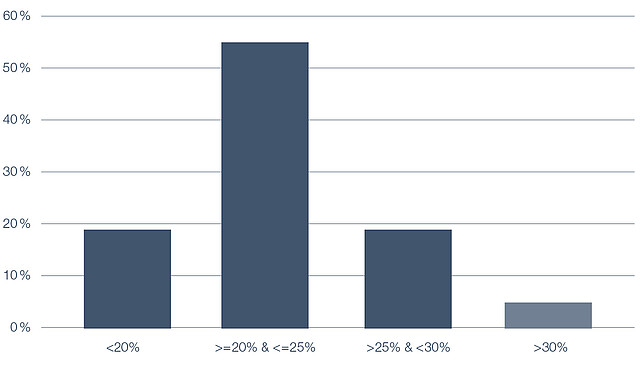

The rising interest rates affect real estate funds quite differently. This mainly depends on their financing structure, i. e. how much borrowed capital they use, and how this borrowed capital is structured. In contrast to stock companies, real estate funds are subject to regulations that limit their borrowed capital to a maximum of one-third. The current weighted average as at the end of January was 23% for the funds included in the SXI Real Estate Funds Broad universe. Not all funds exploited this maximum in the past, for which they were punished by a lower leverage effect. Some funds purposely kept their debt levels high at around 30%, and used short-term financing for almost everything. As shown in Figure 2, around 56% of the index weight have debt levels of 20% to 25%. Seven funds or 6% of the index weight have a leverage ratio of more than 30%. The leverage effect meant that they could still earn an attractive return on equity in spite of falling property yields.

Funds that are still in the development phase had to take up short-term financing in part to maintain their flexibility regarding further acquisitions. The high premiums of the past also allowed these funds to repeatedly reduce their rising debt levels by way of capital increases – which usually happened after lively acquisition activities. Now that premiums are low or in some cases even negative, this strategy is no longer viable. The increased difficulty in accessing equity capital also requires funds to take a more careful and in particular forward-looking approach to their payment obligations in order to avoid having to reduce dividends or sell property.

Consequences of higher interest costs

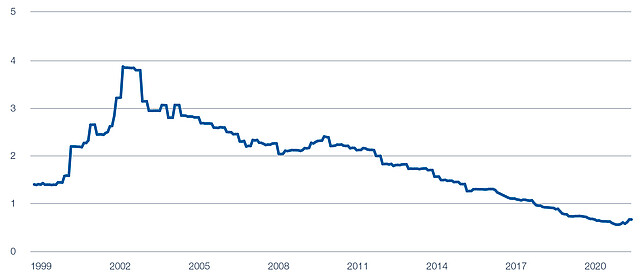

The higher interest costs are already affecting the first half-year and annual statements, as is shown in Figure 3. The extent to which costs are increasing for real estate funds depends on the remaining terms of debt financing. The longer the remaining term, the "more immune" the fund is to rising interest rates. Here too, the funds in the universe are exposed to very diverse terms of a few months to almost six years.

Investors are confronted by the urgent question of how the higher interest costs will impact future returns and thus also the dividend base.

The good news is that the moderate use of debt financing and current financing structure put this asset class in a good position to survive rising interest rates. As shown in Figure 4, the average structure consists of one-third each of short-term, medium-term and long-term debt, which results in a remaining term of 3.3 years at an average cost at present of 0.6%.

<1 year | 1–3 years | 3–5 years | 5–10 years | 10+ years | Total |

38.6% | 14.7% | 15.0% | 29.7% | 2.0% | 3.2 years |

0.5% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.6% |

In an analysis we prepared, which is based on the assumption that the refinancing rate will increase to 2% over the next three years and all other income statement factors will remain the same, the additional interest payment will account for 3.5% of rents or 6.4% of operating cash flow over 12 months, and 4.4% of rents or 8.1% of operating cash flow after three years. In this scenario, around half the funds can keep their operating distribution below 100% and could therefore hold their dividend stable at the current level, and for the other half, a more detailed analysis is required.

A distribution payout ratio of more than 100% does not necessarily mean a reduction in the dividend. Two questions play a role here: Is this due to temporary factors only, such as a delay in rental income due to incomplete construction projects, or rent defaults on properties that have already been re-let? And if the higher distribution payout ratio is not determined by temporary operational reasons, how can the uncovered part of the dividend be compensated?

Realising potential for higher rents

In the short term, funds can take recourse to the cosmetic trick of releasing their retained earnings to improve their net income and maintain the dividend, even though the higher interest rates mean that the dividend is no longer covered. As this would require borrowing more capital, this practice is only possible until the maximum leverage ratio is reached. A more sustainable option would be to increase the rents. In theory, this will happen at the latest by 2024 with the increase in the reference rate for residential properties, provided that the reductions were also always passed on in the past. Forty percent of the increase in inflation can also be added to the rents. For indexed contracts, such as is usual for commercial space, up to 100% of this increase can be passed on in most cases. In practice, however, this is not so easy and depends strongly on local circumstances, in particular on supply and demand and market rents in the relevant region.

Conclusion

After years of ever lower interest costs and easy access to equity capital, real estate funds are now confronted by new challenges. Cost discipline is now more important than financial engineering. The reverse conclusion for investors is that they now have to carry out in-depth analyses and carefully investigate future income trends in view of rising costs for fund companies in order to avoid negative surprises. Our active portfolio management approach defines three specific categories. The winners profit from revenue that is boosted by higher inflation and lower financing costs thanks to defensive financing strategies. The losers' financing costs are rising rapidly and cannot be compensated by additional income. And the income level of those in mid-field can partially or fully compensate for the rise in financing costs.